-40%

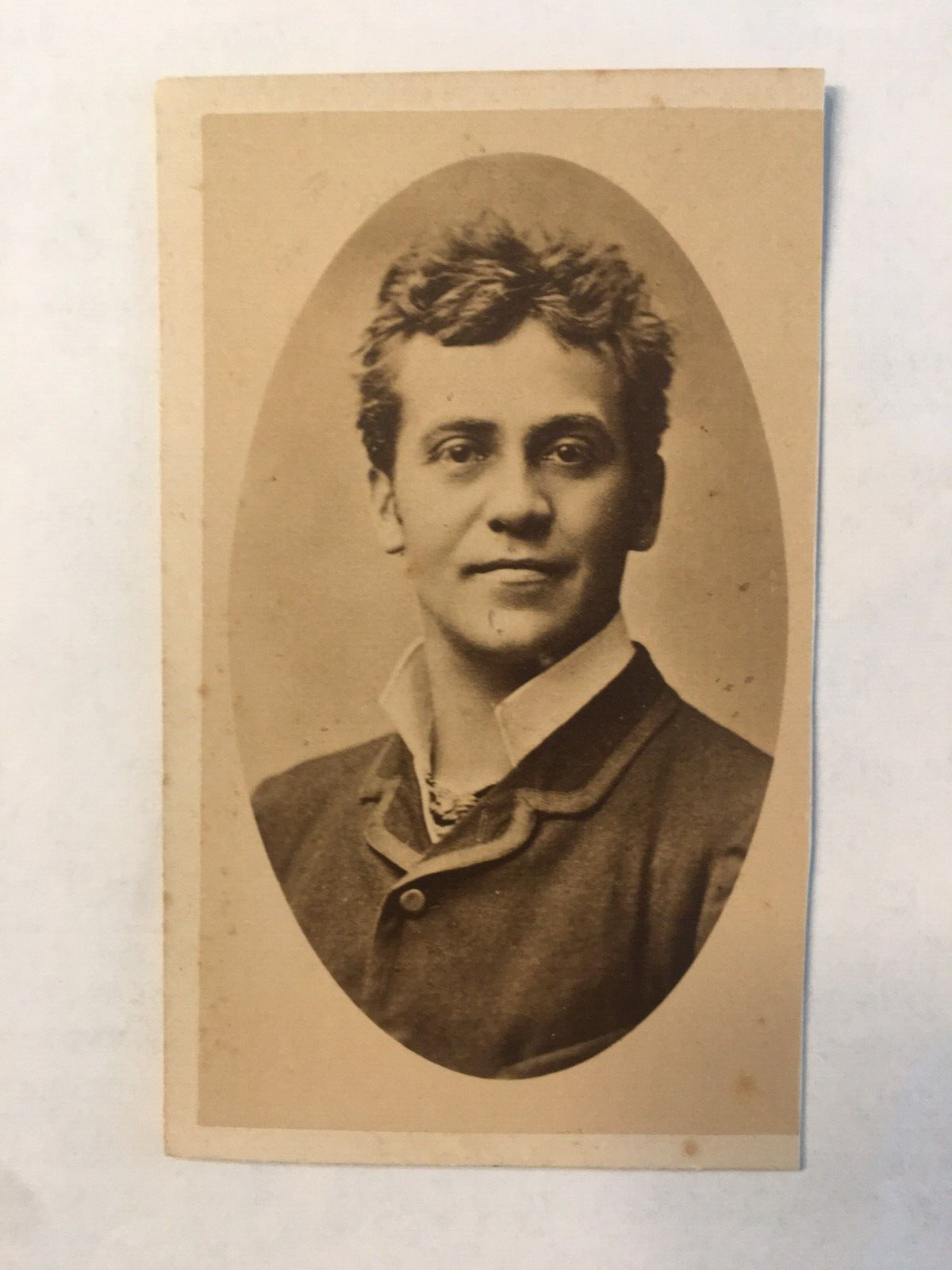

Ignacy Jan Paderewski photo piano pianist

$ 31.67

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

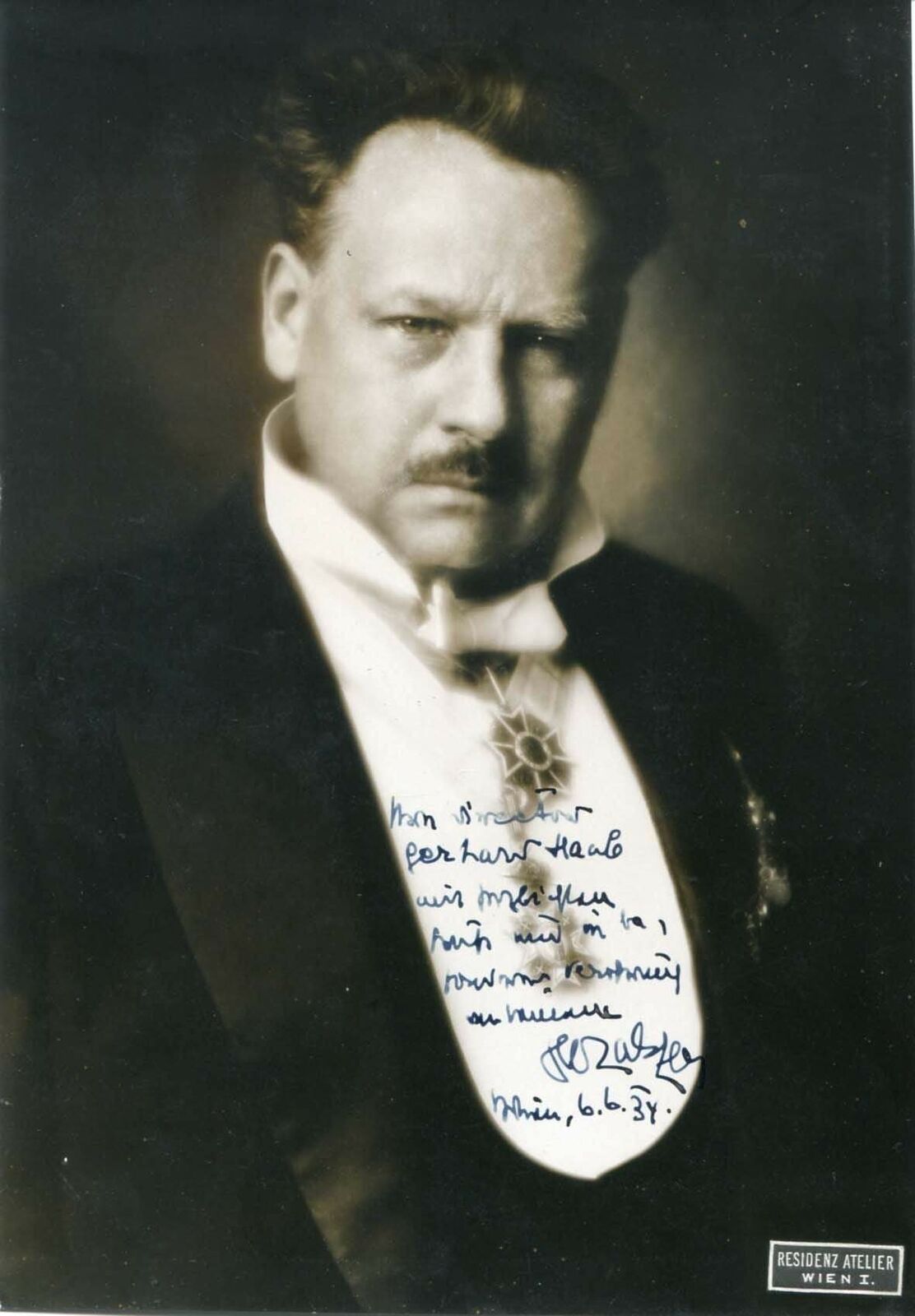

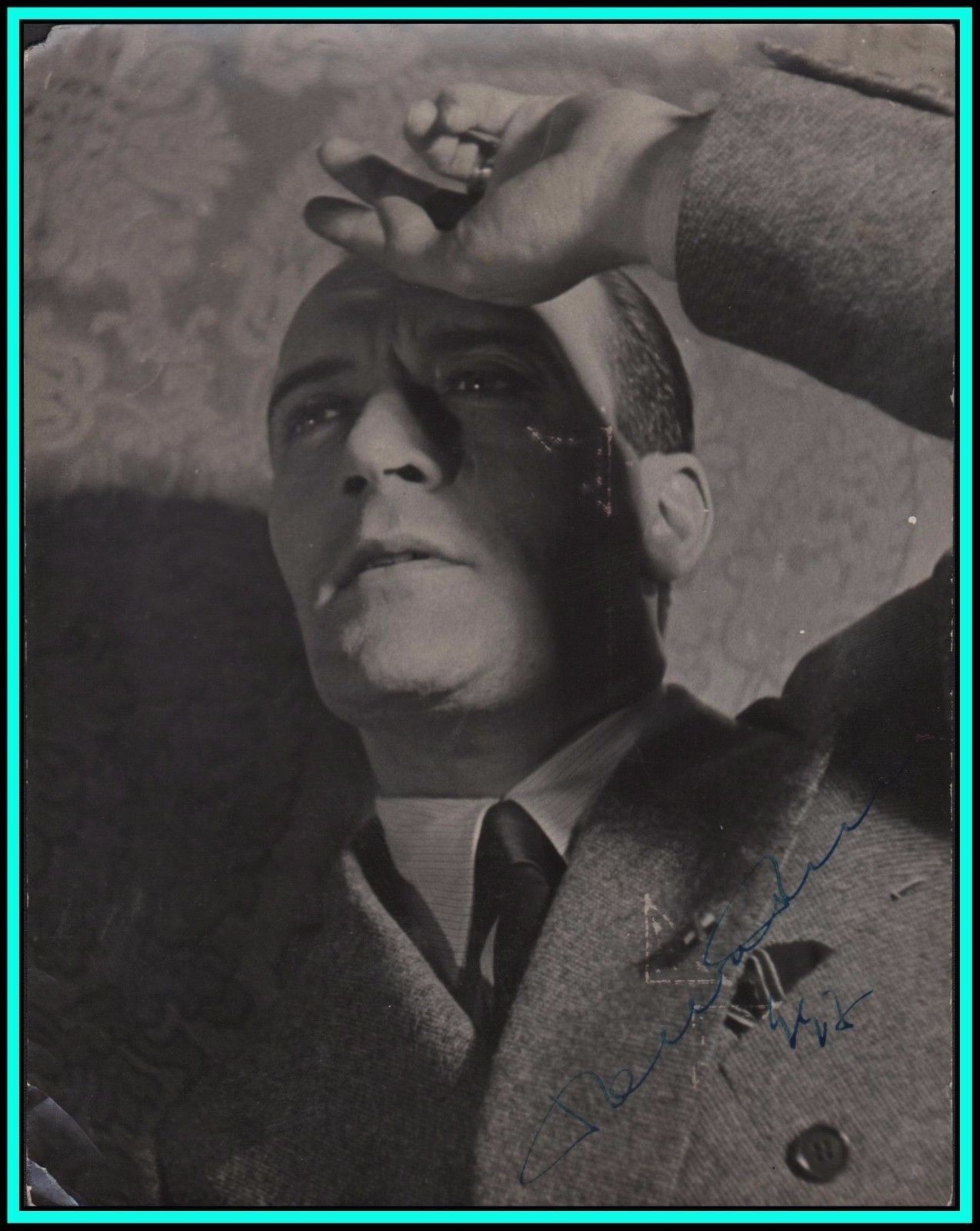

Hello!For sale I have a period photo postcard for the legendary pianist turned prime minister, Ignacy Jan Paderewski. The postcard has been used. It looks like the year is '03 (1903), but I'm not positive. Excellent condition. USPS Priority Mail insured.

I have been a professional violinist for 20 years. I currently teach violin at University of California, Berkeley, and play Concertmaster for the Sacramento Philharmonic and Opera. I've been buying and selling music memorabilia on eBay since it was invented and I've been buying antique art from European and American auction houses for a decade. All pieces for sale are guaranteed authentic and come from my personal collection, which numbers in the thousands.

To learn more about me before buying, visit danflanaganviolin dot com.

Ignacy Jan Paderewski

(18 November [

O.S.

6 November] 1860 – 29 June 1941) was a

Polish

pianist

and

composer

who became a spokesman for Polish independence. In 1919, he was the new nation's

Prime Minister

and foreign minister during which he signed the

Treaty of Versailles

, which ended

World War I

.

[1]

A favorite of concert audiences around the world, his musical fame opened access to diplomacy and the media, as possibly did his status as a

freemason

,

[2]

and charitable work of his second wife,

Helena Paderewska

. During World War I, Paderewski advocated an independent Poland, including by touring the United States, where he met with President

Woodrow Wilson

, who came to support the creation of an independent Poland in his

Fourteen Points

at the

Paris Peace Conference

in 1919, which led to the Treaty of Versailles.

[3]

Shortly after his resignations from office, Paderewski resumed his concert career to recoup his finances and rarely visited the politically-chaotic Poland thereafter, the last time being in 1924.

[4]

Paderewski was born to

Polish

parents in the village of

Kuryłówka

(Kurilivka), Litin uyezd, in the

Podolia Governorate

of the

Russian Empire

. The village had been part of the

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

for centuries and now is part of the

Khmilnyk

raion

of

Vinnytsia Oblast

in

Ukraine

. His father, Jan Paderewski, administered large estates. His mother, Poliksena,

née

Nowicka, died several months after Paderewski was born, and he was raised mostly by distant relatives.

[5]

From his early childhood, Paderewski was interested in music. He initially lived at a private estate near

Żytomir

, where he moved with his father. However, soon after his father's arrest in connection with the

January Uprising

(1863), he was adopted by his aunt. After being released, Paderewski's father married again and moved to the town of

Sudylkov

, near

Shepetovka

.

[6]

Initially, Paderewski took piano lessons with a private tutor. At the age of 12, in 1872, he went to

Warsaw

and was admitted to the

Warsaw Conservatory

. Upon graduating in 1878, he became a tutor of piano classes at his

alma mater

. In 1880, Paderewski married a fellow student at the conservatory, Antonina Korsakówna. The next year, their son Alfred was born severely handicapped. Antonina never recovered from childbirth and died several weeks later. Paderewski decided to devote himself to music and left his son in the care of friends, and in 1881, he went to

Berlin

to study music composition with

Friedrich Kiel

[7]

and

Heinrich Urban

.

A chance meeting in 1884 with a famous Polish actress,

Helena Modrzejewska

, began his career as a virtuoso pianist. Modrzejewska arranged for a public concert and joint appearance in

Kraków's

Hotel Saski to raise funds for Paderewski's further piano study. The scheme was a tremendous success, and Paderewski soon moved to

Vienna

, where he studied with

Theodor Leschetizky

(Teodor Leszetycki).

[8]

[9]

He married his second wife,

Helena Paderewska

(née von Rosen)(1856–1934), shortly after she received an annulment of a prior marriage, on 31 May 1899. While she had previously cared for his son Alfred (1880–1901), they had no children together.

[8]

After three years of diligent study and a teaching appointment in

Strasbourg

which Leschetizky arranged, Paderewski made his concert debut in

Vienna

in 1887. He soon gained great popularity and had popular successes in Paris in 1889 and in London in 1890.

[8]

Audiences responded to his brilliant playing with almost extravagant displays of admiration, and Paderewski also gained access to the halls of power. In 1891, Paderewski repeated his triumphs on an American tour; he would tour the country more than 30 times for the next five decades, and it would become his second home.

[8]

His stage presence, striking looks, and immense charisma contributed to his stage success, which later proved important in his political and charitable activities. His name became synonymous with the highest level of piano virtuosity.

[8]

Not everyone was equally impressed, however. After hearing Paderewski for the first time,

Moriz Rosenthal

quipped, "Yes, he plays well, I suppose, but he's no Paderewski."

[10]

Paderewski kept up a furious pace of touring and composition, including many of his own piano compositions in his concerts. He also wrote an opera,

Manru

, which is still the only opera by a

Polish composer

that was ever performed in the

Metropolitan Opera

's 135-year history. A "lyric drama,"

Manru

is an ambitious work that was formally inspired by Wagner's music dramas. It lacks an overture and closed-form arias but uses Wagner's device of

leitmotifs

to represent characters and ideas. The story centres on a doomed love triangle, social inequality, and racial prejudice (Manru is a

Gypsy

), and it is set in the Tatra Mountains. In addition to the Met,

Manru

was staged in

Dresden

[8]

(a private royal viewing),

Lviv

(its official premiere in 1901),

Prague

,

Cologne

,

Zurich

,

Warsaw

,

Philadelphia

,

Boston

,

Chicago

,

Pittsburgh

and

Baltimore

,

Moscow

, and

Kiev

. In 1904, Paderewski, accompanied by his second wife, entourage, parrot, and Erard piano, gave concerts in Australia and New Zealand in collaboration with Polish-French composer,

Henri Kowalski

.

[11]

Paderewski toured tirelessly around the world and was the first to give a solo performance at the new 3,000-seat

Carnegie Hall

. In 1909 came the premiere of his

Symphony in B minor "Polonia"

, a massive work lasting 75 minutes. Paderewski's compositions were quite popular during his lifetime and, for a time, entered the orchestral repertoire, particularly his

Fantaisie polonaise sur des thèmes originaux

(Polish Fantasy on Original Themes) for piano and orchestra,

Piano Concerto in A minor

, and

Polonia

symphony. His piano miniatures became especially popular; the

Minuet in G major

, Op. 14 No. 1, written in the style of Mozart, became one of the most recognized piano tunes of all time. Despite his relentless touring schedule and his political and charitable engagements, Paderewski left a legacy of over 70 orchestral, instrumental, and vocal works.

In 1896, Paderewski donated US,000 to establish a trust fund to encourage American-born composers. The fund underwrote a triennial competition that began in 1901, the

Paderewski Prize

. Paderewski also launched a similar contest in

Leipzig

in 1898. He was so popular internationally that the music hall duo "The Two Bobs" had a hit song in 1916 in music halls across Britain with the song "When Paderewski Plays". He was a favorite of concert audiences around the globe; women especially admired his performances.

[12]

By the turn of the century, the artist was an extremely wealthy man generously donating to numerous causes and charities and sponsoring monuments, among them the

Washington Arch

, in New York, in 1892. Paderewski shared his fortune generously with fellow countrymen, as well as with citizens and foundations from around the world. He established a foundation for young American musicians and the students of

Stanford University

(1896), another at the Parisian Conservatory (1909), yet another scholarship fund at the Ecole Normale (1924), funded students of the Moscow Conservatory and the Petersburg Conservatory (1899) as well as spas in the

Alps

(1928), for the

British Legion

. During the Great Depression]], Paderewski supported unemployed musicians in the United States (1932) and the unemployed in

Switzerland

in 1937. Paderewski also publicly supported an insurance fund for musicians in London (1933) and aided Jewish intellectuals in Paris (1933). He also supported orphanages and the Maternity Centre in New York. Only a few of the Paderewski-sponsored concert halls and monuments included

Debussy

(1931) and

Édouard Colonne

(1923) monuments in Paris,

Liszt

Monument in Weimar,

Beethoven

Monument in Bonn, Chopin Monument in

Żelazowa Wola

(the composer's birthplace),

Kosciuszko

Monument in Chicago, and Washington Arch in New York.

[13]

California

In 1913, Paderewski settled in the

United States

. On the eve of

World War I

and at the height of his fame, Paderewski bought a 2,000-acre (810-ha) property, Rancho San Ignacio, near

Paso Robles

, in

San Luis Obispo County

, in California's Central Coast region. A decade later, he planted

Zinfandel

vines on the Californian property. When the vines matured, the grapes were processed into wine at the nearby

York Mountain Winery

, which was, as it still is, one of the best-known wineries between

Los Angeles

and

San Francisco

.

In 1910, Paderewski funded the

Battle of Grunwald

Monument in Kraków to commemorate the battle's 500th anniversary. The monument's unveiling led to great patriotic demonstrations. In speaking to the gathered throng, Paderewski proved as adept at capturing their hearts and minds for the political cause as he was with his music. His passionate delivery needed no recourse to notes. Paderewski's status as an artist and philanthropist and not as a member of any of the many Polish political factions became one of his greatest assets and so he rose above the quarrels, and he could legitimately appeal to higher ideals of unity, sacrifice, charity, and work for common goals.

During

World War I

, Paderewski became an active member of the

Polish National Committee

in Paris, which was soon accepted by the

Triple Entente

as the representative of the forces trying to create the state of Poland. Paderewski became the committee's spokesman, and soon, he and his wife also formed others, including the Polish Relief Fund, in London, and the White Cross Society, in the United States. Paderewski met the English composer

Edward Elgar

, who used a theme from Paderewski's

Fantasie Polonaise

[15]

in his work

Polonia

written for the Polish Relief Fund concert in London on 6 July 1916 (the title certainly recognises Paderewski's Symphony in B minor).

Paderewski urged fellow Polish immigrants to join the Polish armed forces in France, and he pressed elbows with all the dignitaries and influential men whose salons he could enter. He spoke to Americans directly in public speeches and on the radio by appealing to them to remember the fate of his nation. He kept such a demanding schedule of public appearances, fundraisers, and meetings that he stopped musical touring altogether for a few years, instead dedicating himself to diplomatic activity. On the eve of the

American entry into the war

, in January 1917, US President Woodrow Wilson's main advisor,

Colonel House

, turned to Paderewski to prepare a memorandum on the Polish issue. Two weeks later, Wilson spoke before Congress and issued a challenge to the status quo: "I take it for granted that statesmen everywhere are agreed that there should be a united, independent, autonomous Poland." The establishment of "New Poland" became one of Wilson's famous

Fourteen Points

,

[3]

the principles that Wilson followed during peace negotiations to end World War I. In April 1918, Paderewski met in New York City with leaders of the

American Jewish Committee

in an unsuccessful attempt to broker a deal in which organised Jewish groups would support Polish territorial ambitions, in exchange for support for equal rights. However, it soon became clear that no plan would satisfy both Jewish leaders and

Roman Dmowski

, the head of the Polish National Committee, who was strongly anti-Semitic.

[16]

At the end of the war, with the fate of the city of

Poznań

and the whole region of

Greater Poland

(Wielkopolska) still undecided, Paderewski visited Poznań. With his public speech on 27 December 1918, the Polish inhabitants of the city began a military uprising against Germany, called the

Greater Poland Uprising

. Behind the scenes, Paderewski worked hard to get Dmowski and

Józef Piłsudski

to collaborate, but the latter came on top.

In 1919, in the newly independent Poland, Piłsudski, who was the

Chief of State

, appointed Paderewski as the

Prime Minister of Poland

and the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Poland (January 1919 – December 1919). He and Dmowski represented Poland at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference and dealt with issues regarding territorial claims and minority rights.

[17]

He signed the

Treaty of Versailles

, which recognized Polish independence won after World War I, and the subsequent Soviet invasion was halted.

Paderewski's government achieved remarkable milestones in just ten months: democratic elections to Parliament, ratification of the Treaty of Versailles, passage of the treaty on protection of ethnic minorities in the new state and the establishment of a public education system. It also tackled border disputes, unemployment, ethnic and social strife, the outbreak of epidemics and averted the looming famine after the devastation of war. After the elections, Paderewski resigned as prime minister but continued to represent Poland abroad at international conferences and at the

League of Nations

. Thanks to his diplomatic skills (he was the only delegate who was not assigned a translator since he was fluent in seven languages) and great personal esteem, Poland was able to negotiate thorny issues with its Ukrainian and German neighbours and gain international respect in the process. In 1922, Paderewski retired from politics and returned to his musical life. His first concert after a long break, held at

Carnegie Hall

, was a significant success. He also filled

Madison Square Garden

(20,000 seats) and toured the United States in a private railway car.

In 1897, Paderewski had bought the manor house of the former Duchess of Otrante near

Morges

,

Switzerland

, where he rested between concert tours.

[20]

After Piłsudski's

coup d'état

in 1926, Paderewski became an active member of the opposition to

Sanacja

rule. In 1936, two years after his second wife's death at their Swiss home, a coalition of members of the opposition met in the mansion and was nicknamed the

Front Morges

after the village.

By 1936, Paderewski agreed to appear in a film that presented his talent and art. Although the proposal had come while the mourning Paderewski avoided public appearances, the film project went ahead. It became notable, primarily, for its rare footage of his piano performance. The exiled German-born director

Lothar Mendes

directed the feature, which was released in Britain as

Moonlight Sonata

in 1937 and re-titled

The Charmer

for US distribution in 1943.

[21]

[22]

In November 1937, Paderewski agreed to take on one last piano student. The musician was

Witold Małcużyński

, who had won third place at the

International Chopin Piano Competition

.

[23]

Return to politics

After the

Polish Defensive War

in 1939, Paderewski returned to public life. In 1940, he became the head of the

National Council of Poland

, a Polish

sejm

(parliament) in exile in London. He again turned to America for help and spoke to its people directly over the radio, the most popular media at the time; the broadcast carried by over 100 radio stations in the United States and Canada. In late 1940, he spent a couple of weeks in Portugal, before returning to the United States. He stayed in

Estoril

, at the Hotel Palácio, between 8 October and 27 October 1940.

[24]

Afterwards, he crossed the Atlantic again to advocate in person for European aid and to defeat Nazism. In 1941, Paderewski witnessed a touching tribute to his artistry and humanitarianism as US cities celebrated the 50th anniversary of his first American tour by putting on a Paderewski Week, with over 6000 concerts in his honour. The 80-year-old artist also restarted his Polish Relief Fund and gave several concerts to gather money for it. However, his mind was not what it had once been, and scheduled again to play Madison Square Garden, he refused to appear and insisted that he had already played the concert; he was presumably remembering the concert he had played there in the 1920s.

In 1897, Paderewski had bought the manor house of the former Duchess of Otrante near

Morges

,

Switzerland

, where he rested between concert tours.

[20]

After Piłsudski's

coup d'état

in 1926, Paderewski became an active member of the opposition to

Sanacja

rule. In 1936, two years after his second wife's death at their Swiss home, a coalition of members of the opposition met in the mansion and was nicknamed the

Front Morges

after the village.

By 1936, Paderewski agreed to appear in a film that presented his talent and art. Although the proposal had come while the mourning Paderewski avoided public appearances, the film project went ahead. It became notable, primarily, for its rare footage of his piano performance. The exiled German-born director

Lothar Mendes

directed the feature, which was released in Britain as

Moonlight Sonata

in 1937 and re-titled

The Charmer

for US distribution in 1943.

[21]

[22]

In November 1937, Paderewski agreed to take on one last piano student. The musician was

Witold Małcużyński

, who had won third place at the

International Chopin Piano Competition

.

[23]

After the

Polish Defensive War

in 1939, Paderewski returned to public life. In 1940, he became the head of the

National Council of Poland

, a Polish

sejm

(parliament) in exile in London. He again turned to America for help and spoke to its people directly over the radio, the most popular media at the time; the broadcast carried by over 100 radio stations in the United States and Canada. In late 1940, he spent a couple of weeks in Portugal, before returning to the United States. He stayed in

Estoril

, at the Hotel Palácio, between 8 October and 27 October 1940.

[24]

Afterwards, he crossed the Atlantic again to advocate in person for European aid and to defeat Nazism. In 1941, Paderewski witnessed a touching tribute to his artistry and humanitarianism as US cities celebrated the 50th anniversary of his first American tour by putting on a Paderewski Week, with over 6000 concerts in his honour. The 80-year-old artist also restarted his Polish Relief Fund and gave several concerts to gather money for it. However, his mind was not what it had once been, and scheduled again to play Madison Square Garden, he refused to appear and insisted that he had already played the concert; he was presumably remembering the concert he had played there in the 1920s.

[18]